Antimicrobial activities of Streptomyces collected from Con Dao and Phu Quoc primitive forests

- School of Biotechnology, International University, Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

- Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam

Abstract

Streptomyces species, especially antimicrobial compounds, are among the major organisms used for natural biochemical production. However, less is known about these species in primitive regions. From 39 soil samples collected in different forest sites on Phu Quoc (PQ) and Con Son (CD) Islands, Viet Nam, 103 Streptomyces isolates were observed on the selective solid medium ISP4. After continuous subculture to pure microbes, the Streptomyces isolates were observed and classified by microscopic and biochemical tests. Using a well diffusion technique, the antimicrobial activities of the ethyl acetate extracts from broth cultures of all the isolates were preliminarily examined against 6 microbes, namely, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus flavus, which are gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria, yeast and fungi, respectively. Antimicrobial tests of ISP4 crude extracts from 103 isolates derived from both forests revealed 54 isolates (52.4%) with activity, and these isolates were present in different groups of aerial mycelia. Among them, eleven isolates exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects on more than 2 indicators, among which isolates P24 and P66 exhibited activity against 4 of the 6 tested microorganisms. These results indicate the antimicrobial potential of the isolates from both primitive forests under these laboratory conditions. This observation reveals promising resources for further investigation of this organism for antibiotic discovery.

INTRODUCTION

species are characterized as gram-positive aerobic bacteria with typical growth and complex anatomic forms. A spore germinates under the right conditions to generate a vegetative mycelium. Under extreme conditions, some substrate hyphae (vegetative mycelia) start growing into the air, where they can form aerial mycelia. At the time, the substrate mycelium undergoes a process of programmed cell death, and concurrently, its content is reused by the growing aerial mycelium. Finally, the partition process is complete with the step of the sporulation stage, yielding beautiful chains of spores in which the heritable content is a single genome. Substrate and aerial hyphae are immotile; however, their mobility could be disrupted by the dispersion of spores 1. These morphological properties are basically useful for characterization.

While there are several microorganisms, such as , and , that can produce potent antimicrobial compounds, is still renowned as the largest genus that produces broad-spectrum antimicrobial substances and is an industrially potential microbial group for new antibiotics. More than 80% of antibiotics are produced by this group of microorganisms 3. Identifying and exploring strains with antimicrobial activity to obtain additional novel active compounds are therefore the most integral parts of scientific research.

According to some studies, a few soil strains have been reported to be found in coastal regions; these strains exhibit high and good antimicrobial activity against common pathogens that cause plague in plants 1, 4. Several marine species have also been shown to produce secondary metabolites, many of which are good antibiotics that have been screened recently 5. In addition, the marine environment is a largely unexploited source of new antibiotics because of the enormous diversity of microorganisms that produce secondary metabolites4, 6. Research on in Vietnam has been carried out in different ecological areas, including coastal and terrestrial regions. However, less is known about protected zones where there is no or little exchange activity. This investigation aimed to first explore the use of resources on two islands, Phu Quoc and Con Dao, where natural ecosystems are primitive and diverse. All the obtained isolates were also screened for collection and antimicrobial activity to evaluate their potential against microbes under laboratory conditions. The results from this project will contribute to further study of antimicrobial compounds produced by this bacterium species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and pretreatment of soil samples

Thirty-nine different soil samples were collected around the coastal regions of Phu Quoc Island (Kien Giang) and Con Son Island (Ba Ria Vung Tau) Con Dao. Samples were taken mostly from areas along the seashore at depths varying approximately 10 centimeters or near the trees. The samples were air-dried and cleaned by solid sieving to eliminate degrading parts of animals and tree products (trunk, leaf, etc.). ), nylon, and other nonbiodegradable substances. One gram of each soil sample was suspended in 10 mL of 0.9% NaCl (Duchefa Biochemie, Neitherland) solution, shaken vigorously for 30 minutes, and then serially diluted. A total of 100 mL of the aliquot of each diluted sample was plated on ISP4 agar medium (Himedia, India) for isolation in a safety cabinet. The ISP4 agar plates were incubated at 28°C and observed continuously for two weeks to determine the presence of colonies7.

Isolation of microbial cultures and storage

The selective medium ISP4 was used to inoculate soil aliquots and differentiate distinct strains of sp. 8. After collection, all the isolates were subcultured to make them purer and observed for one week. The -like isolates were further characterized morphologically and physiologically by following the methods given in the International Project (ISP)8, 9. The aerial hyphae, substrate mycelia, and spore chains were observed and determined via light microscopy examination of the cultures after 4 days of growth at 28°C and via a Gram staining test. Concurrently, a stereomicroscope was used to determine the colony size, color, boundary, and general appearance. Due to the complex secondary metabolism pathway, sp. may present various colors in this medium: white, black, brown, red, and yellow 10. Bacterial isolates were classified as if the colony surface was hard, dry, or smooth with a clear and distinct border. At the late stage of development, colonies develop a yarn of aerial hyphae that look floccose, granular, powdery, or velvet11. The Gram-staining technique was applied to determine the gram-positive characteristics of In addition, the spore chain morphology and sporulation type of the isolates were recorded following the classification instructions in the research of Qinyuan Li

Organic crude extracts

Isolates were cultured in 100 mL of ISP4 broth medium in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask on a shaker working at 120 rpm at 25°C within 4 days 13. In a previous study, after testing with different media, 4 days of incubation in ISP4 medium was considered the optimal time for supernatant collection; the culture media were centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 minutes at 25°C to collect the supernatants for antimicrobial activity testing 14.

Ethyl acetate–EtOAc (AR, Xilong, China) is a colorless solvent that has a sweet smell and low polarity compared with water. This solvent is recommended as the prioritized solvent over other solvents for extraction due to its reasonable price and low toxicity 15. The culture filtrate was extracted with the solvent ethyl acetate at a ratio of 1:1 (v/v) 13 and was continuously shaken gently for 45 minutes. The organic fraction was separated from the aqueous phase and concentrated by evaporation to complete dryness under a chemical hood14. One milliliter of autoclaved distilled water was subsequently added to obtain the extract from the broth culture.

Preliminary antimicrobial activity test

After ethyl acetate extraction, the organic fractions of the culture were subjected to antimicrobial tests against 6 common microbes: , , , . The antimicrobial activity was determined by using the agar well diffusion method and measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone (mm). One hundred microliters of the obtained extract from each isolate was added to each well on LB agar plates (Himedia, India) 16, 17. A negative control (sterilized water) and a positive control (ciprofloxacin 128 µg/mL and nystatin 250 µg/mL) 18 were also included in each test. Tested microbes with a concentration of 106 CFU were spread adequately and smoothly on agar plates and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 120 hours. Antimicrobial activity was noted when the extracts displayed a clear inhibition zone against microorganisms in comparison with the controls. The selected isolates that displayed broad-spectrum activity were then re-examined in triplicate.

Data analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The data were analyzed via ANOVA using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software, with p ≤ 0.05 indicates significant difference.

The average germination time of Streptomyces isolates.

Gram staining of representative

Sporophore morphology of

Sporulation types of

RESULTS

Isolation of

From 39 soil samples, 78 isolates were obtained from Phu Quoc Island and named P1 to P78, while 25 isolates were collected from Con Son Island and named C1 to C25. These isolates were observed and collected based on the following categories: germination time, aerial hyphal color, substrate color, colony features, and spore chain morphology.

Germination time was recorded at the appearance of aerial hyphae (secondary mycelia) on the solid medium surface. Owing to these characteristics, species can be divided into fast-, medium-, and slow-growing groups. In our samples, colonies grew slowly during the incubation stage, and aerial hyphae were observed only after 48 hours on agar plates (Figure 1). Most of the isolates developed aerial hyphae after 48 hours of incubation, whereas 33 and 27 isolates spent 64 hours and 72 hours developing aerial hyphae, respectively.

All the isolates were well developed on ISP4 media, and their colors varied among the strains. Streptomyces-like isolates were grouped by distinct aerial and substrate mycelium colors (

Colors distribution in aerial hyphae and substrate mycelium of isolates

|

Aerial hyphae |

Substrate mycelium | ||||

|

Color |

No. isolates |

% |

Color |

No. isolates |

% |

|

Brown |

7 |

6.7 |

Brown |

19 |

18.4 |

|

Gray |

16 |

15.4 |

Dark green |

3 |

3 |

|

Olive |

1 |

1 |

Gray |

10 |

9.7 |

|

Pink |

1 |

1 |

Greenish gray |

4 |

3.9 |

|

Red |

3 |

3 |

Olive |

2 |

1.9 |

|

White |

53 |

51.4 |

Orange |

5 |

4.8 |

|

White‒brown |

10 |

9.7 |

Pink |

3 |

3 |

|

White‒gray |

3 |

3 |

Red |

2 |

2 |

|

White‒pink |

1 |

1 |

White |

35 |

34 |

|

Yellow |

8 |

7.8 |

Yellow |

20 |

19.3 |

|

Total |

103 |

100% |

Total |

103 |

100% |

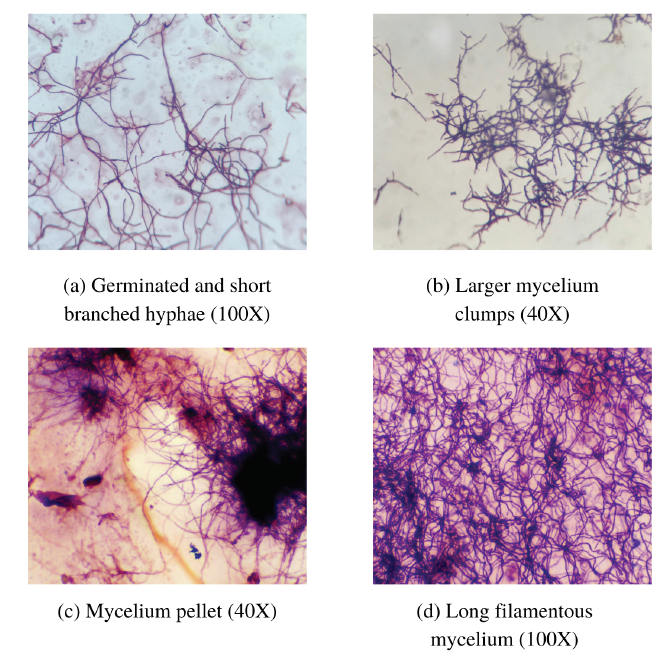

Apart from colony morphology, Gram staining was carried out carefully to distinguish potent candidates from fungi and other bacteria. The right isolates were stained with a dark blue‒purple color as indicated by the corresponding size. After Gram staining, all the isolates were observed to have coenocytic vegetative mycelia, which produced filamentous and profusely branched mycelia with net-like structures (Figure 2). Mycelial differentiation was observed between the primary and secondary mycelial stages as follows: initial germination and formation of branched hyphae (Figure 2 a), formation of larger clumps (Figure 2 b), and the formation of mycelial pellets (Figure 2 c) with long filamentous mycelia (Figure 2 d). Based on Gram staining, the sporophore morphologies of the Streptomyces isolates were also noted as follows: rectus flexibilis, spira, retinaculiaperti, compact coiled, and long coiled mycelia (Figure 3).

The sporulation pathways of the isolates were also recorded (Figure 4), and all the strains were fragmented into hyphal compartments that contained numerous copies of chromosomes (forming spore chains before dispersing around the environment) (Figure 4 a). However, mycelium cutting occurred in different ways. The compact coiled and long coiled mycelia separated themselves at the cross wall on their secondary mycelium (Figure 4 b), which was similar to spiral mycelia cutting itself along the spore chain and forming rings (Figure 4 c). Moreover, the rectus-flexibile mycelia were twisted, and some regions were cut into hyphal compartments, which subsequently formed spores. In the last sporulation type, the retinaculiaperti mycelium forms a loop at one end of the mycelium to generate spores (Figure 4 d).

Antimicrobial activity

The filtrate extracts from 103 isolates initially showed that 52.4% (54 isolates) of the total collected isolates produced bioactive compounds against the tested microbes.

Antimicrobial potential of 103 Streptomyces isolates against 6 microbes

|

Tested microbes |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

E. coli |

B. subtilis |

C. albicans |

A. flavus | ||||||

|

Location |

CD |

PQ |

CD |

PQ |

CD |

PQ |

CD |

PQ |

CD |

PQ |

CD |

PQ |

|

Number of isolates |

- |

11 |

7 |

23 |

- |

2 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

17 |

1 |

- |

|

Percentage (%) |

- |

10.7 |

6.8 |

22.2 |

- |

2 |

4.9 |

1.9 |

3 |

16.5 |

1 |

- |

|

10.7 |

29 |

2 |

6.8 |

19.5 |

1 | |||||||

Among the colonies with white aerial and substrate mycelia, 51.8% and 37%, respectively, had white aerial and substrate mycelia, and the isolates with this mycelial color mostly had antimicrobial activity. However, the antimicrobial properties of the isolates were present in all the color groups (

Colors in aerial hyphae/substrate mycelium of potential Streptomyces isolates

|

Aerial hyphae |

Substrate mycelium | ||||

|

Color |

No. isolates |

% |

Color |

No. isolates |

% |

|

Brown |

1 |

1.9 |

Brown |

9 |

16.7 |

|

Gray |

11 |

20.3 |

Dark green |

3 |

5.5 |

|

Olive |

1 |

1.9 |

Gray |

4 |

7.4 |

|

White |

28 |

51.8 |

Greenish gray |

3 |

5.5 |

|

White‒brown |

9 |

16.6 |

Olive |

1 |

1.9 |

|

White‒gray |

1 |

1.9 |

Orange |

2 |

3.7 |

|

White‒pink |

1 |

1.9 |

Pink |

2 |

3.7 |

|

Yellow |

2 |

3.7 |

White |

20 |

37 |

|

Yellow |

10 |

18.5 | |||

|

Total |

54 |

100% |

54 |

100% | |

After preliminary antimicrobial testing, 11 isolates were re-examined and exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity (

Antimicrobial activity of selected

|

Inhibition zone diameter (mm) | ||||||

|

Isolate ID |

P. aeruginosa |

S. aureus |

E. coli |

B. subtilis |

C. albicans |

A. flavus |

|

Positive control |

30±0.0c |

29±0.0b |

35±0.0b |

40±0.0e |

24±0.0b |

16±0.0a |

|

P24 |

24.3±1.2b |

24.7±0.9b |

14±0.6a |

- |

19.3±1.2a |

- |

|

P66 |

15±0.6a |

24±1.2b |

15±0.3a |

13±0.6a |

27±1.5c |

- |

|

P27 |

- |

- |

- |

26.7±0.3d |

18±0.0a |

- |

|

P60 |

15.3±0.3a |

23±0.6b |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

P67 |

- |

26.7±0.9b |

- |

- |

19±0.6a |

- |

|

C3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18±0.0a |

14±0.35a |

|

C11 |

- |

17±0.0a |

- |

17±0.0b |

- |

- |

|

C19 |

- |

25±0.0b |

- |

23.3±0.3c |

- |

- |

|

C21 |

- |

22.2±0.3b |

- |

22±0.0c |

- |

- |

|

C22 |

- |

21±0.0b |

- |

- |

23±0.0b |

- |

|

C24 |

- |

15±0.6a |

- |

23.8±0.12c |

15±0.0a |

- |

DISCUSSION

isolates usually germinate after 48–168 hours. Under laboratory maintenance conditions, should be cultured and observed on solid media for 4 to 7 days and stored at 4°C for 8 weeks19. In previous studies, Ahmed I. Khattab collected 50 isolates from soil sediments after 4–7 days of incubation 20. Similarly, Antonieta Taddei also collected 71 Streptomyces isolates after 48, 72, and 96 hours of incubation with different aerial hyphal colors, including gray, white, red, yellow, green, blue, and violet 21. Longer and different germination times not only helped us not to miss any isolate but also assisted us in initially distinguishing Streptomyces colonies from other bacteria and fungi that easily grow on solid media after 24 hours of incubation. Moreover, researchers have shown that there is likely a relationship between morphological differentiation and biosynthesized product accumulation 22, 23. For example, prodigiosin and actinorhodin are produced by at the secondary mycelium stage24. On solid media, after a few days, aerial hyphae appear, the peripheral regions of the colony will grow more, while other regions start secondary metabolism and produce antibiotics for self-protection of their nutrients from exploitation by neighboring microbes25. The inhibition zone could then be observed; therefore, this time point should be considered when the researcher intends to perform a cross-streak method for antimicrobial screening.

The aerial hyphae and substrate mycelium colors were recorded as taxonomic characteristics. Since several active compounds extracted from are colored, the color of the mycelia partially reflects the biochemical characteristics of the bacteria14, and these findings can be used to characterize these microbes25, 26. After more than a week after the aerial hyphae had germinated, the isolates were aged and experienced cell death. At that time, the colonies turned dark, and the spores started dispersing to initiate a new lifecycle. In some studies, melanoid production and the production of other soluble pigments were also observed as additional criteria in combination with the above criteria to classify and name strains. For example, isolates that produce melanin and have a yellowish substrate mycelium and red soluble pigment with spiral spore chains could be or 9 on peptone-yeast extract ion agar (ISP6) and tyrosine agar (ISP7) 27, 9, 7. The culture criteria, such as the traditional approaches described in the International Project (ISP), which include spore chain morphology, the color of aerial hyphae and vegetative mycelia, soluble pigment and melanoid production, and biochemical characteristics, are used as the initial steps in differentiating from other bacteria and fungi27. The presence of these pigments indicates that the secondary metabolism of these isolates, such as pigmentation antibiotics or enzyme production, is active14. Thus, the antimicrobial activity of the isolates collected in this study were continuously screened, and those isolates were selected for further studies.

The isolates from Phu Quoc showed higher activity than those from Con Dao in the test against most microbes. In total, the number of isolates with antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria was greater than that against gram-negative bacteria in both collections; in particular, many isolates inhibited . However, no Con Dao isolate was able to stop the growth of or when cultured in ISP4 medium. Similarly, no isolate from the Phu Quoc forest was able to prevent infection during the primary screening of antimicrobial activity.

Although the number of antimicrobial isolates with white aerial and substrate mycelial colors dominated in this collection, the isolates with antimicrobial properties were present in all the color groups (

This study suggested that ISP4 medium was good for isolation; however, it was not useful for antibiotic production. In further studies, these isolates should be cultured in different optimized media or extracted via different methods for antibiotic production. The relationship between antibiotic production and pigmentation mechanisms should be further investigated.

CONCLUSION

From 39 soil samples, 103 isolates were collected and stored in 30% glycerol at -80°C. All the isolates were grown well in ISP4 media. The germination time of the isolates varied from 48 hours to 120 hours; however, most of the collected populations developed aerial hyphae within 48 hours to 72 hours. Moreover, the isolates displayed diverse colors, and the color of the substrate mycelia developed differently from that of the aerial hyphae. Moreover, the color can change under different environmental conditions. The white color of the aerial and substrate hyphae was prevalent in this collection. This finding suggested that ISP4 medium is related to the mechanism of white pigmentation in this collection. The morphology of the isolates changed from simple short branched mycelia to larger clumps, which subsequently formed mycelial pellets. Although there are five types of sporulating mycelia, they all cut their hyphal compartments to form spores that disperse around the environment to start a new lifecycle. Fifty-four isolates showed potential for antimicrobial compound production against the 6 listed microbes. Most of the isolates exhibited antimicrobial activity, and when cultured in ISP4 medium, they produced secondary metabolites against at least one of the microbes; moreover, 11 promising isolates exhibited broad-spectrum signals. These isolates should be studied further for molecular identification and optimization of culture conditions for antibiotic production.

LIST OF ABBREVIATION

CFU: Colonies Forming Unit

EtOAc: Ethyl acetateg Gramhr Hour

ISP: International Project

LB: Luria–Bertani

mL: Milliliter

rpm: Rounds per minute

S.:

Species

TSB: Tryptic Soy Broth

µg: Microgram

µl: Microliter

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was funded by The International University Research Fund.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Tran Ngoc Thang isolated and tested bacteria from Phu Quoc and prepared the manuscript; Truong Hoa Thien and Le Pham Hoai Thuong isolated and tested bacteria from Con Dao. Tong Thi Hang collected the samples, discussed the research results and completed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.