Measuring the efficiency of the Republic of Korea’s cultural diplomacy in Vietnam under Moon Jae-in’s presidency (2017-2022) and its potentialities

- Department of Liberal Arts Education, University of Management and Technology, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Abstract

As soon as the new president of the Republic of Korea was elected in 2017, Moon Jae-in anchored the New Southern Policy (NSP), which targeted southern Asian countries and expanded South Korea’s strategic presence in the Asia-Pacific Ocean. As such, the ROK continued to adopt a public diplomacy policy and empowered Korean culture in Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam. This article aims to generalize Moon Jae-in’s policy on cultural diplomacy and his application in Vietnam as a case study. I employed Joseph Nye’s soft power and cultural diplomacy concept while adopting a qualitative method to collect official information from the ROK’s homepages and assess diplomatic results. The central argument of this article is that Moon Jae-in considers cultural diplomacy a key element of the NSP for promoting Korean culture and bolstering a strategic presence in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. The ROK attempted to graft K-pop, movies, Korean customs, Korean languages, and Korean cuisine onto the Vietnamese concept and seek an upgrade of Vietnamese Korean cultural exchanges and the frequent organization of cultural events. Hence, an upgrade between the ROK and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in December 2022 marked an achievement of cultural diplomacy. I also argued that this attempt has a tonic effect on continuing the ROK cultural diplomacy under Yoon Suk Yeol’s presidency and on the foreseeable chance of both the SRV and the ROK in cultural diplomacy.

INTRODUCTION

From a foe in the Vietnam War, the Republic of Korea (ROK) restored its influence in Southeast Asia and established a partnership with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) on December 22, 19921. Simultaneously, the arrival of the ROK was concomitant with the open-door policy of the SRV, which dismantled its blockage and merged into a regional and international environment. Thereafter, the ROK and the SRV made strenuous attempts to establish economic and political collaboration and upgraded this relationship step-by-step, pushing the ROK into the ASEAN market and lifting it to a higher position in this region.

Seen as a developed country that has achieved a miracle Han River, the ROK thrived across decades and became the 13 rank of the most developing economy in the world2. In addition to having an enormous economic advantage, the geographical expansion of Hallyu also showed that Seoul concentrated on fostering a new concept of influential Korean culture, along with the landing of giant Korean enterprises in the Vietnamese market, such as Samsung, LG Electronics, or Hyundai3, 4. Globalization can be explained as a major tendency of state foreign policy and can facilitate the prevalence of culture in a borderless sphere. Considering this phenomenon as an economic preference that involves the intervention of countries and NGOs in international affairs5 or a mutual dependence of all countries on an economic development purpose 6, as well as placing great emphasis on a shared global market7, globalization has reached a further extent of influence on imposing cultural interference in international relations. In this case, Vietnam appeared to be a ripe area for ROK cultural interference. Emerging as a giant state of popular culture, the Korean Wave or Hallyu was introduced to Vietnamese people in the late 20 century. Touching and romantic Korean dramas were broadcasted and won Vietnamese people’s hearts, which showed that Korean cultural industries come to fruition in this country8.

This situation should be viewed as a reciprocal process when both the SRV and the ROK strived to accelerate cultural exchanges. In particular, the ROK Ministry of Foreign Affairs publicly spewed out a statement that cultural expansion, as well as a given priority of cultural exchanges between the ROK and its partners, should be identified9, although some historians still viewed economic collaboration as major attention of Seoul when patching up with its partners 10. Notably, the Korean Wave adopted its second application in the early 2010s because Korean music enjoyed its popularity in the Vietnamese market. Children learned how to sing and perform as Korean singers, and Korean celebrities were fully idolized by some young Vietnamese listeners. This may be because Seoul was cognizant of Korean soft power11, and in 2015, it was stated that its foreign policies not only benefited from an official channel of government but also made room for nongovernmental organizations, public culture in arts, knowledge sharing, media, language, and financial aid. These elements stimulated the growth of public diplomacy and asserted its centrality in the ROK’s foreign policy12. In addition, Vietnamese Communist leaders also deemed the ROK to be a strategic partner for enhancing economic collaboration and enhancing mutual public diplomacy. As the SRV interpreted, this was a promotion of mutual understanding and participation in cultural globalization as built into the Cultural Diplomacy strategy in 2011 and 202113. Therefore, both Hanoi and Seoul viewed cultural diplomacy as a splendid chance to empower their culture in this bilateral relationship.

In 2017, Moon Jae-in was elected as the new president of the ROK. On the first visit to Indonesia in November 2017, Moon adopted his maiden statement of the New Southern Policy (NSP) to advance the ROK’s strategic interests in South Asia and Southeast Asia14, which emphasized his major focus on strongly upgrading his relationships with ASEAN members and opening new windows of opportunity for technological, heritage, and people exchanges. On this occasion, Moon referred to people/public diplomacy, which is known as the tremendous capacity of the ROK to expand the Korean sphere and boost mutual understanding between the ROK and its partners. While under pressure to overcome economic problems and achieve economic habilitation, the ROK, a middle-power country, also expressed its simmering dream of balancing major powers and reinforcing its geopolitical position in Southeast Asia. When raising this question about its bilateral relationship with Hanoi, Moon also saw his advantages in sharing cultural similarities and long-standing historical contact between Korea and Vietnam, which also supported Seoul’s cultural diplomacy in Southeast Asia. Ending the presidency in 2022, it is critical to reassess what Moon attempted to achieve in his administration on cultural diplomacy with Hanoi and what kinds of legacy for his successor to elevate this diplomacy in a bilateral relationship with the SRV. Therefore, I will reply to two primary research questions of this article:

-

How did Moon Jae-in perceive pivotal Southeast Asia and Vietnam in his NSP’s cultural diplomacy, and how did Hanoi respond to this policy? As a result, I will re-evaluate the efficiency of bilateral cultural diplomacy activities between Seoul and Hanoi under the Moon Jae-in administration.

-

What were the advantages and disadvantages of those activities? Therefore, what is predicted for this relationship in the future?

LITERATURE REVIEW

The cultural diplomacy between the ROK and the SRV enjoyed a well-trodden academic background. There is much debate on recent developments in the NSP in the Southeast Asian environment and Vietnam. Those papers are concerned with the ROK’s economic and political connectivity in ASEAN countries and the adaptation of Seoul to Sino-American rivalry in the Asia Pacific Ocean. Kadir Ayhan (2017)15 draws on some specific characteristics of Korea’s soft power and public diplomacy under the presidency of the Moon Jae-in. The Hallyu phenomenon was sufficient to maintain Korea’s appearance in Seoul’s public diplomacy; the author paid close attention to the coordination between the Foreign Ministry and other ministries and culture departments to implement a strategy for Seoul to enlarge its cultural expansion overseas. The establishment of the Public Diplomacy Committee is a glaring illustration of governmental attempts to succeed in this plan. However, Kadir also has a clear indication of a deficit in the thematic analysis of Korea’s cultural diplomacy and how to translate plans of cultural diplomacy into a reality of implementation15. Min Sung Kim also stated that Moon Jae-in had political implications when performing Korean soft power overseas. Contributing to international relations on the grounds of the NSP, which promoted people, peace, and prosperity, Moon Jae-in promoted Korean economic thriving and transformed exceptional technological advances of South Korea in the Southeast Asian market, so it is also a great advantage to build up democratization and reinforce geopolitical influences of the ROK in Southeast Asia and Vietnam16. Soft power plays a complementary role in restoring the hard power of South Korea and accelerating the speed of ROK engagement in culture in ASEAN countries and Vietnam, which could be devoted to creating a favorable environment for the ROK’s geopolitical and economic position in Vietnam. In addition, a strong connection between economic aims and soft power is also analyzed in “South Korean Diplomacy Between Domestic Challenges and Soft Power” when Jan Melissen and Hwa-Jung Kim deemed soft power an attractive tool for Moon Jae-in. Seoul could combine domestic and foreign audiences to nurture public diplomacy, and the administration was ready to operate the Center for Public Diplomacy and allocate a considerable amount of funds to expand Korean culture overseas. Moon’s diplomatic practices have a great focus on domestic listeners and viewers, although the Moon administration has attempted to tap into uncovered areas of Korean public diplomacy worldwide17.

As a target of the ROK’s soft power, the relationship between Hanoi and Seoul has created much debate in Vietnamese literature. When investigating the efficiency of the NSP, Phạm Quý Long and Nguyễn Thị Phi Nga (2022)18 assumed that the NSP created a sweeping change in ROK public diplomacy and that the NSP Plus (NSP 2.0) heavily focused on two aspects of Korean educational and cultural exchanges between the ROK and ASEAN members19. By combining the NSP with Northern Policy in culture, Seoul asserted the significance of peace, collaboration, and dialog for achieving territorial reunification. However, a misconception of its partner power and overdoing Hallyu will likely challenge the NSP that Seoul tried to leverage cultural exchange only from the ROK side. With a diversity of soft powers in Southeast Asia, Seoul is facing difficulties in rallying its soft power in this region, while Hallyu is shifting its focus to other continents. In addition, Moon Jae-in built a collegial environment for the ROK in Southeast Asia thanks to the availability of five objectives and twelve strategies sketched by the ROK Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The ROK’s capacity for public diplomacy was filled by two-sided cultural exchanges, the involvement of knowledge on all aspects of Korea, and the promotion of Korea’s nation-branding in international relations. As Tống Thuỳ Linh interpreted, this was a typical example of the new version of ROK public diplomacy since the ROK MOFA strengthened the perception of the formidable capacity of ROK public diplomacy through the mobilization of people support, financial allocation, and the expansion of public diplomacy agencies20. Furthermore, Moon was capable of reshaping his public diplomacy in ASEAN countries because these societies scarcely suffered from colonial historical obsessions by China or Japan. While partnering with ASEAN members to address social maladies and promote cultural exchange, a major impediment of Seoul is that Seoul still has superficial knowledge of Southeast Asian cultures and imposes the Korean Wave in both its cultural and economic sections21. Moreover, Nguyễn Thị Thắm (2014)22 indicated four major impacts of the Hallyu phenomenon on Vietnam. The growth of Hallyu created a dynamic market of Korean product consumption and promoted the Hanoi-Seoul trade relationship. In addition, this situation has stimulated the generous allocation of the ROK economy to Vietnam and led to a competitive foreign economy in this country22. When viewing this aspect, Seoul has a considerable advantage in manipulating its economic influence in the Vietnam market while exhibiting Korean culture in Vietnam as a foreseeable outcome if the Moon utilizes this influence in a subtle and effective way.

In general, augmenting research arguments on this topic, the efficiency of ROK cultural diplomacy has persisted in historiography. The constellation of related research papers clarified Moon Jae-in’s approach to the NSP and his application to strategic areas, such as South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. The transformation of the NSP into two versions did not limit the chances for ROK public diplomacy, and the Moon Jae-in administration dealt with this category in an efficient manner when he energized the operation of the Public Diplomacy Committee and continued strategic plans of Seoul on public diplomacy from his predecessors. Nevertheless, cultural diplomacy is a subsection of public diplomacy, and in some cases, this category dominates over the other aspects. Mentioning culture as an enormous benefit of ROK public diplomacy, Moon hardly refers to cultural diplomacy in much detail. Southeast Asia is a pivotal area of ROK public diplomacy, but Seoul has a distinctive way of implementing cultural diplomacy for each ASEAN member. There is still a dearth of studies on the case of Vietnam and how the SRV responded to Seoul’s policy, as well as what is associated with this relationship under the new presidency of Yoon Suk Yeol.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This paper relies on what historians and politicians interpret as “soft power,” which is deemed a state instrument and control over another state by its cultural power and promoted by people-to-people contact. There is a strong linkage between soft power and cultural diplomacy. In essence, cultural diplomacy has a well-established historical account because its origin should be dated back to cultural exchange between war, annexation, and exodus. Nevertheless, globalization, as an emergent phenomenon in the second half of the 20 century, ramped up astonishly when people-to-people exchange was preferred and the ease of immigration and mobilization energized cultural exchanges. In addition, the adaptation of states to globalization triggered a wide adaptation of open-door policy, and this situation has room for cultural absorption; this approach is utilized as a kind of power to help a state advance its appearance in international relations.

In particular, there is growing controversy about cultural diplomacy in the literature. While soft power has many functions, it can be reflected in cultural exchanges among states. Culture is a pattern of soft power that consists of art, movies, music, cultural traits, and customs. When the international sphere enjoys new circumstances, the use of hard power is insufficient to gain full benefit internationally. Joseph Nye has a clear indication of the role of soft power when another state probably appreciates foreign values and encourages people to follow them23. Values indicate the cultural and historical aspects of a country. This power turned out to be an enormous advantage for a state that has a preference for long-standing culture and identities and consequently promotes national branding. Similarly, the U.S. Department of State also asserted the significance of cultural diplomacy when executing diplomacy because it is likely to present national ideas and impose influence on another state. in subtle, wide-ranging, and sustainable ways24. According to this definition, cultural diplomacy is a subsection of national public diplomacy, and a state may promote a growing influence by organizing additional cultural activities and educational exchanges with its partners. Milton Cummings also indicates that cultural diplomacy is the process of exchanging ideas, information, art, and other cultural aspects to foster mutual understanding and promote national language and local identities25. The role of culture is underlined, as it contributes to promoting national branding and achieving peace, cooperation, and development. While facing the challenge of miscommunication and misunderstanding, a state can adopt a policy on deeper public diplomacy to amend those disadvantages through open dialog. Moreover, Simon Mark (2009)26 highlighted four key elements of cultural diplomacy, namely, governmental involvement, state objectives, cultural activities, and the audience of those activities26. While public diplomacy is merely general in people-to-people contact, cultural diplomacy strongly emphasizes the role of culture and requires a comprehensive policy from the government to graft national culture into diplomatic activities and arouse the interest of other states in cultural identities; as a consequence, the state is effortless to gain economic, commercial, and political interests. This kind of diplomacy coordinates with other categories to upgrade diplomatic power and has a strong correlation with a higher position of a state in international relations. However, it is also noticeable that a state may reach its extent to implement its cultural diplomacy, which should rely on the availability of its distinguished identities and state policies on national cultural preservation and influences on its image.

In brief, cultural diplomacy is a subset of public diplomacy and is a performance of national soft power. We should avoid misunderstanding these distinctive definitions. In some cases, cultural diplomacy is considered optimal for a state to build its national branding in international relations and sow seeds of cultural influence in other countries. A state conducts this kind of diplomacy in a governmental effort to organize cultural events or encourage cultural exchanges and reach a mutual agreement on culture in state diplomatic activities. This kind of diplomacy not only lifts a state’s position and helps achieve political and economic implications but also has a tonic effect on national cultural preservation and enriches national identities.

METHODOLOGY

I adopted a qualitative research design and chronologically arranged events to determine progress and to easily assess the efficiency of diplomatic activities. Concerning sources of material, a great volume of information was extracted from the official homepages of the SRV Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Culture Department of the ROK Embassy in Vietnam; this information was combined with news and articles in daily newspapers and existing statements of previous articles and analyses regarding this issue. Subsequently, all the data were processed via textual analysis and thematic analysis, which explain the political and diplomatic implications of both states and processes according to soft power norms to expound the underlying principles of the Mon Jae-in administration in operating this cultural diplomacy with the SRV and its influence on the presidency of his successor.

RESULTS

Moon Jae-in and the New Southern Policy in Cultural Diplacy and the Position of Vietnam in Terms of This Policy

Fully elected after Park Geun Hee, Moon Jae-in was missioned to consolidate national democracy and settle political turbulence for fear that Park’s corruption tarnished South Korean nation-branding. Under his presidency, Moon Jae-in spewed out the “New Southern Policy,” with two major versions, 1.0 and 2.0, which generally focus on expanding the ROK’s international relations with the purpose of nurturing collaborative interdependence and creating a new idea of South Korea’s central position27. Accordingly, Seoul heightened the importance of its relationship with ASEAN members. A trade-off approach was taken for major powers in the Asia-Pacific Ocean, such as the United States, China, Japan, and Russia.

There are three underpinnings of the NSP, namely, people, peace, and prosperity28. Considering people as a top priority of this policy, Moon underscores the significance of people’s values and attempts to build a collaborative environment of human resources and preserve regional security for the safety of South Korea. The NSP targets a tendency toward economic development, stimulates the growth of the Korean economy in Southeast Asia, and strongly affiliates with US strategies in the Asia-Pacific Ocean. Despite not saying about cultural diplomacy, this approach shows that Seoul has thought about harmonious development, which incorporates political and diplomatic implications and a greater reputation for the ROK in nation branding. From this view, Moon paid substantial attention to Southeast Asian countries. As soon as it was inaugurated in late 2017, Moon undetook his formal visits to three countries in this region and stated that ASEAN became one of the critical partners of the ROK and that Seoul would create a strenuous attempt to upgrade bilateral and multilateral relationships with ASEAN members29. Consequently, the ROK cultural diplomacy became one of the main springss of a higher position in Southeast Asia, and this kind of diplomacy has the formidable capacity to advance in this region due to its lingering effect through the Hallyu phenomenon.

In particular, the role of cultural diplomacy was raised in Moon Jae-in’s discussions. In 2017, initial changes in public diplomacy by the ROK were thoroughly debated, and the First Basic Plan on Public Diplomacy (2017-2021) sketched a map of further steps taken by Seoul to embark on Southeast Asia’s environment. In this event, public diplomacy was perceived as a specific way to spread Korean values and boost a mutual understanding of collaborative projects. In addition, Hallyu would be ongoing, and the government would promote Korean language courses and culture overseas. However, public diplomacy implementers in consultancy with the Foreign Ministry must conduct these practices to navigate the policy and hinder the possibility of adverse outcomes that would undermine Korean values30. This discussion highlights the need for a concerted effort between this agency’s Foreign Ministry and Public Diplomacy Committee to coordinate public diplomacy activities. A grave concern about the role of public diplomacy is the greater responsibility of the Moon Jae-in administration for restoring the significant influence of the Korean Wave in the Asia-Pacific Ocean. While public diplomacy is viewed as a general agenda of culture, education, language, and immigration policy, culture probably plays a central role in exhibiting Korean culture and repeating the colorful history of the Korean Wave in the Asia–Pacific Ocean. As explicitly declared, Korean public diplomacy actors currently include the national government, governmental agencies, local governments, and private sector participants31. This is a collective effort of the ROK government to construct a coordination system to enhance the tactical presence of the ROK via public diplomacy in international relations. Moreover, Seoul also outlined four key elements of national public diplomacy, including continuing Hallyu and disseminating current knowledge on Korean culture and history overseas. To fulfill this mission, Seoul assigned its worldwide embassies to offer Korean-language courses and Korean studies32. Although culture has not been referred to as a separate section of national public diplomacy, a forefront objective to promote Korean culture overseas and governmental concern about the role of culture implied a resolve to reach a geographical appearance in Asia—the Pacific Ocean—which is considerably challenged by other cultures, such as China, Japan, India, and the US.

Paying special attention to Southeast Asia in the NSP, Seoul does have a tremendous advantage in questioning Vietnam about a higher level of relationships in culture. This historical account was recorded for the first time during a visit to Yi Yong-sang (a Vietnamese Ly dynasty noble), and his outstanding contribution to Korean history was recorded during the Goryeo dynasty33. The two countries underwent a rough history of annexation and national division due to the civil war, so cultural and historical similarities are one factor in building an organic relationship. Established in 1992 and experiencing globalization as a common phenomenon, the SRV and the ROK focused on economic collaboration, and Hanoi gave legal permission to South Korean giant enterprises to allocate their massive investment in the Vietnam market34. Recently, there has been a growing presence of Korean research institutes and reciprocal cultural events between the SRV and the ROK, and these activities have become a typical example of Seoul’s application of Korean soft power in Vietnam. The open-door policy of the SRV from 1986 and a publication of the 2011 Vietnamese Culture Diplomacy accelerated the speech of cultural exchanges and created a large window for the penetration of the Korean Wave into Vietnam at a higher level. In 2021, Hanoi continued to put cultural exchanges in high regard and proposed that this kind of diplomacy would diversify Vietnamese cultural identities, while this concept was lifted to “Vietnamese soft power” in the 13 Congress of the Vietnam Communist Party in 202135. Hanoi placed its cultural exchanges with Seoul in high swings on a road to translate “a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” into reality. This benefit considerably assisted Moon Jae-in’s administration in firmly engaging with ASEAN members, including Vietnam, in his strategic NSP.

The Exhibition of the Republic of Korea’s Cultural Diplomacy in Vietnam (2017-2022): A Revisit

The first signal of the ROK’s cultural diplomacy lies in frequent art performance events when Seoul assigned several artist groups to Vietnam to perform Korean folk and modern arts. Theoretically, these cultural events are disguised as political instruments and give artists and singers a tremendous chance to perform their work for a broader audience36. On the occasion of marking 25 years of the Hanoi-Seoul relationship, the Vietnam–Korea Music Festival in Hanoi was organized and attracted singers from Vietnam and South Korea to showcase folk music and national identities to viewers37. Subsequently, on November 28, 2018, the ROK General Consulate cooperated with the Vietnam Department of Commerce and Industry to commence “The Festival of Trade and Culture Exchanges between Vietnam and South Korea”. According to Lim Jae Hoon, Head of the ROK General Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City, this event would stimulate cultural exchanges and expand Korean presence in the Vietnamese market, as well as boost the value of exports and imports between South Korea and Vietnam38. This is a great mingling of culture and economy because Seoul entertained the capacity of the NSP when promoting Korean goods and products to Vietnamese consumers and inculcated Korean cultural images into Vietnamese concepts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the ROK still successfully organized a cultural exchange fair (KV Culture Fair 2020) in Hanoi on November 30, 2020. This event was moderated by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, the Vietnamese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI), and the Korean Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs of Korea, the Korean Embassy in Vietnam, and the Korea Agricultural, Fisheries and Food Distribution Corporation. With a showcase of 56 food stalls and a vivid atmosphere of Korean culture, Vietnamese viewers experienced Korean cuisine culture and enjoyed Korean folk culture39. Subsequently, the ROK restored its cultural presence in Vietnam after the national lockdown of Vietnam and ceased international commercial fights when the ROK moderated the Vietnamese-Korean cultural exchange festival at the International Conference in Hanoi on November 11, 2022, on a key occasion of the 30-year bilateral relationship establishment40. Moreover, the Vietnam–Korea Cultural Trade and Investment Exchange Week in Ho Chi Minh City was also organized from October 28 to November 1, 202241. Happening after the COVID-19 pandemic, this event was a chance for both the SRV and the ROK to restore their policy on cultural exchanges and target economic rehabilitation in trade. Additionally, organized on the threshold of the 30-year friendship anniversary, the event performed a series of folk cultures of both Vietnam and South Korea, appealed for mutual understanding, and backed the ROK economic plans in the post-COVID-19 pandemic. The continuing occurrence of cultural events shows that cultural diplomacy is a coherent policy used by Seoul to greatly boost its sense of connectivity in Vietnam and the ASEAN. Moon after, Jae-in divided this mission into the ROK Embassy and General Consulate in Vietnam to uphold the significance of cultural exchange activities, and this mission enjoys a special role in conveying a message of the ROK in favorable Korean goods in the context of rival commercial competition in the Vietnamese market. Fruitful collaborations have also occurred between the ROK Foreign Ministry and other ministries, as well as overseas ROK embassies, to transplant Korean culture into local countries through cultural diplomacy activities.

In addition, the cultural diplomacy of the ROK is reflected in Korean NGO organizations in Vietnam, and there has been a merger of cultural events in local provinces of Vietnam, which designed a landscape of Korean culture in many parts of this country. In particular, in 2019, the South Korean Institute of Economic Revival and Association of Taego Buddhism held the Vietnam–South Korea Cultural Exchanges, which attracted more than 80 Vietnamese and Korean artists to perform their work on mutual identities when both Vietnam and Korea experienced a long-standing history of the Sinosphere and a massive influence of Buddhism42.

Simultaneously, the Vietnam–South Korea Cultural Exchange Festival took place in Đà Lạt, Lâm Đồng Province, Vietnam, on the occasion of the Dalat Flower Festival in December 2019, with a repertoire of 20 Vietnamese and Korean performances from Qwangju and Chucheon43. In 2020, in collaboration with the Lao Cai People Committee, the ROK Embassy in Vietnam organized the Korean Culture Festival in Sapa, a town where Korean culture was unfamiliar to indigenous people. However, this event came to fruition since it attracted several international and Vietnamese tourists to enjoy the Korean sphere and advertised localities to tourists44. In 2021, the Art Federation of Chungbuk Province also organized an event to promote Korean culture through calligraphy, art exhibitions, folk culture, and music in Phú Yên, Vietnam, on the basis of a mutual Chungbuk-Phu Yen memorandum45. In the middle of 2021, the ROK Embassy also coorganized Korean Day with the People Committee of Quảng Nam Province, Vietnam, performing Korean folk culture and advertising Korean tourism to local attendants46. Revisiting Seoul’s strategies, these continuing events were a glaring example of the ROK public diplomacy infrastructure because Seoul indicated its attempts to establish an international public diplomacy network. “Knowledge” public diplomacy was one of the three pillars of Seoul’s strategies for public diplomacy; Moon Jae-in opened up a vista at both the state level and local level to heighten a total sense of Vietnamese people’s Korean culture. As such, it seems less challenging for the Moon to boost the ROK’s economy and investment in local provinces of Vietnam, and Vietnamese laborers view the ROK as an ideal destination for their careers. Despite its strong influence, the ROK cultural diplomacy has had considerable implications for the Korean economy in an attempt to reinforce its power in the Vietnamese market.

Furthermore, Moon Jae-in’s administration outlined that the availability of ROK NGOs in Vietnam and a series of activities by the Korean Culture Center and the Korean Foundation are immensely helpful for Moon’s new public diplomacy strategy. Pouring more than 300 billion KRW in public diplomacy, Moon appeals to a collective effort of multiple departments to conduct national public diplomacy in full swing. The role of the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism (MSCT) was additionally strengthened by additional agencies: the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), the Korea Foundation (KF), and the Overseas Korean Foundation (OKF)17, which showed that public diplomacy plays a vital part in the southern march of the Moon administration in Southeast Asia and Vietnam. The Korea Foundation engaged in several collaborative events with Vietnam’s universities to subsidize a curriculum of Korean studies in Vietnam. In 2021 and 2022, the Korea Foundation, respectively, achieved a memorandum with the Vietnam National University in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City47, which showed a commitment between the Foundation and the University to increase the quality of Korean studies, build Korea reading rooms, and publish Korean-language books and journals in Vietnam. In addition, the Korea Foundation held seminars on Korean studies to promote the use of the Korean language and culture for Vietnamese high school teachers48. This activity was meaningful to local high schools, who floated on teaching the Korean language as a subject in the curriculum. When revisiting Korea’s goals in public diplomacy, sharing and deepening Korean culture are two main elements of gaining populous support for ROK power and cultivating sympathy for the ROK’s overseas policy. Moon’s administration enlarged the Korean cultural presence in Vietnam, which is on par with the ROK’s economic and political engagement in Southeast Asia. Moon’s preparation for an upgrade between Seoul and Hanoi in 2022 also explains this incremental progress. This is straightforward evidence of a peak level of bilateral relationships in an attempt to tie Seoul to Southeast Asia. Eventually, this plan was confirmed in his final year of presidency. While Hallyu no longer lies in its central position in Asia, the role of K-POP still has a lingering effect, as has the expansion of Korean cuisine culture in Vietnam. The Korean Culture Center (KCC) operation in Hanoi designed a vast range of Korean cultural events, classes, and shows for Vietnamese people. The Vietnamese people have a chance to learn the Korean language and participate in cultural exchange programs between South Korea and Vietnam. Furthermore, this center offered participants some Minhwa arts courses, Hanbok paper flowers, and other types of Korean art performances. For example, in 2019, the Korean Culture Center (KCC) organized a class on the Korean cuisine experience. In 2020, this center organized weekly cookery classes for Vietnamese learners and chefs who wanted to become master chefs in Korean food. Additionally, KCC organizes a wide range of K-POP classes called the K-POP Academy. K-POP has a significant impact in Vietnam, and Vietnamese students in major cities with K-POP have attempted to tap into extracurricular courses. These activities contributed to building a sense of Korean culture in the Vietnamese context. In the midst of soft power competition, Moon faced a diminishing Hallyu in Asia and a deeper engagement of other Asian cultures in Vietnam; he still expressed vital concern about the higher level of Korean cultural engagement in Vietnam and strengthened a robust relationship with Hanoi in his NSP strategy.

In general, Moon Jae-in’s NSP asserted his centrality in the growing influence of the ROK in Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries but saw a range of cultural diplomacy developments. Compared to his predecessors, Moon Jae-in continued to foster an awareness of both hard power and soft power when approaching Southeast Asian countries and deepened the sense of Korean presence in the economy and culture of this region. Meanwhile, Hanoi seems open-minded enough to give permission to the ROK to make its strategic appearance in Vietnam and propel cultural exchanges to success. A joint effort to mobilize a collaboration of the ROK’s agencies while actively working with Hanoi to rivet its economic partnership was seen as a success of Moon Jae-in’s public diplomacy and Korean culture overseas.

What is the Scenario?

Moon terminated his presidency in May 2022, but what he achieved in public diplomacy may have left an exciting premise for his successor, Yoon Suk Yeol. Despite the influence of the new international context, Yoon is expected not to alter the Moon’s NSP in public diplomacy. The sharing of Korean history, traditions, culture, and vision while rallying the collective support of governmental and nongovernmental agencies to give public diplomacy a lift32. Resting on the long and cordial basis of the Seoul–Hanoi relationship, the new ROK government is likely to salvage from its available advantageous position in Vietnam to elevate Korean culture and promote the image of South Korea in this country to make room for further economic presence in the Vietnamese market and Southeast Asia.

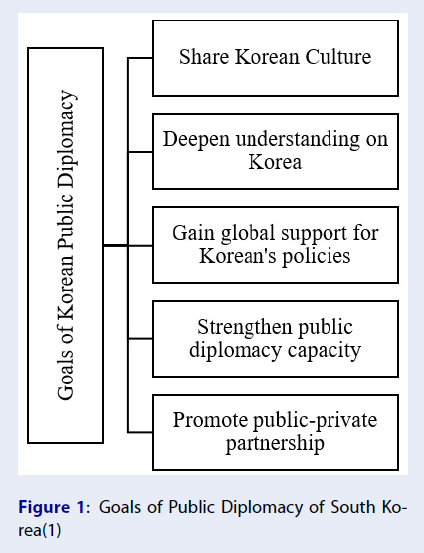

Goals of Public Diplomacy of South Korea (1).

Until late 2022, the ROK still had a disposition toward five elements of national public diplomacy. It is essential that sharing Korean culture enjoys the priority of public diplomacy, which will push the Korean wave in Vietnam forward. Korean culture influences young Vietnamese people, and the current presence of the Korean language and studies is highly beneficial for helping Seoul take further steps. With the rapid growth of the Korean cultural industry, Korean cultural products are in sufficient condition to be consumed in Vietnam due to Hanoi-Seoul’s economic commitment. The continuing operation of the KCC, KF, and KOICA probably plays a central role in exhibiting Korean culture in Vietnam at a higher level of involvement. The ROK’s cultural assets are displayed in cultural events, cultural exchanges, and academic courses for Vietnamese people; these agencies continue to circulate in Korean culture and have a major influence on diplomacy and education. In addition, the high activity of ROK embassies in Vietnam could lead to national festivals and cultural events between South Korea and Vietnam to promote Korean culture and tourism at both the state and local levels, which would seize a large area of Korean culture in Vietnam. It would also strengthen the position of the ROK’s soft power to achieve a balanced geopolitical structure in Southeast Asia.

The growing influence of the ROK’s cultural diplomacy is beneficial for international advocacy for ROK foreign policy32. The upgrade of the Hanoi-Seoul bilateral relationship set a firm foundation for Seoul to execute an expansionist goal. However, Seoul must specify critical objectives of the ROK cultural diplomacy and provide fresh instructions to implement them in a specific country. Public diplomacy and cultural diplomacy are two distinct definitions of diplomacy. While public diplomacy has a broad range of aspects, cultural diplomacy is dedicated to cultural aspects. When setting up a cultural diplomacy agency with Vietnam, the ROK needs to understand historical and cultural accounts inside. In this current commitment, it is difficult to distinguish between what Seoul conducted for ASEAN countries and what it conducted for Vietnam. The diffusion of Korean culture in Vietnam occurred from a single side in Seoul, while Hanoi did not take advantage of this involvement to bolster Vietnamese culture in South Korea or to sign additional memoranda to make Vietnamese Korean cultural exchanges at the highest level. According to the results of this case study, both Hanoi and Seoul need to take further action to build up their soft power and perform this on both sides.

In addition, it is expected that the ROK will exhibit art performance and promote Korean studies in Vietnam in the coming years. In addition to the consumption of Korean musical products in Vietnam, the ROK will continue to collaborate with the SRV government to organize annual Vietnamese Korean festivals, and Seoul will closely work with the SRV to give Korean expatriates in Vietnam some priority. This is also a joint effort between the SRV and ROK ministries to both give permission for the presence of Korean culture in parts of Vietnam and energize Korean NGOs in Vietnam to show certainty and the actual existence of Korean culture in Vietnam.

Finally, Seoul is likely to rely on the Overseas Korean Foundation (OKF) to stimulate the growth of Korean culture in Korean expats in Vietnam. Seoul would provide assistance to Korean expats to promote Korean culture through communal events and festivals organized in Vietnam by embassies and consulates or engage with Korean NGOs to moderate conferences, seminars, and sponsorship programs to back the ROK in cultural diplomacy strategies in Vietnam. Recently, the appearance of K-towns in major cities, such as Ho Chi Minh City, created a hub for Korean expats in Vietnam and became a job market for Korean and Vietnamese people49. In the future, Korean expats will likely be encouraged by the ROK Embassies and General Consulate, as well as by the legal permission of the SRV to construct new areas for Korean people in business and education. This approach is also helpful for the penetration of Korean culture in Vietnam.

CONCLUSIONS

This article is concerned with the efficiency of Moon Jae-in’s administration in cultural diplomacy through the case study of Vietnam. On the basis of online evidence, previous articles and framed theoretical approaches to soft power and qualitative methods, I argue that the ROK’s cultural diplomacy under Moon Jae-in’s presidency was in full swing, and the final foot of this relationship was that Seoul gained a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” with Hanoi in 2022. Moon’s NSP heightened the importance of the political and economic presence of the ROK in the Asia-Pacific Ocean, but he utilized cultural diplomacy to shape a comprehensive understanding of Korean culture in the Asia-Pacific Ocean. Moon after, Hanoi had the advantage of pivoting this aspect because Hanoi’s policy remained open to the ROK, and both countries experienced several cultural and historical similarities. Despite not adopting a specific policy dedicated to Vietnam, Seoul’s cultural diplomacy was conducted in three aspects, namely, at the state level, at the local level, and at the operation of Korean NGOs and governmental sponsored organizations. These activities fulfilled the geostrategy of Seoul to support a multifaceted collaboration with Hanoi, and eventually, a comprehensive strategic partnership was achieved. Although no longer seizing political power, Moon’s cultural diplomacy has several clear indications of extending Seoul’s cultural diplomacy under Yoon Suk Yeol’s presidency. In particular, Seoul is expected to take a main thrust to bilateral commitments in annual festivals and cultural exchanges at both the state and local levels. In addition, Seoul is likely to formulate a specific policy on Seoul’s cultural diplomacy and what actions should be implemented for Vietnam rather than as a general agency of current public diplomacy. In the new context of international relations, Seoul would pay much attention to the Public Diplomacy Committee, governmental and nongovernmental organizations overseas, the ROK embassy and general consulate in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City to organize Korean language courses and cultural events and prioritize Korean studies in Vietnam. Furthermore, a pattern of Korean hubs in major cities in Vietnam has full potential to support the possibility of accessing the ROK’s cultural diplomacy in Vietnam.

ABBREVIATIONS

NSP: New Southern Policy

ROK: the Republic of Korea

SRV: the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

KRW: Korean Won

MSCT: The Republic of Korea Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism

KOICA: the Korean International Cooperation Agency

KF: the Korea Foundation

OKF: Overseas Korean Foundation

KCC: The Korean Culture Center

NGOs: nongovernmental organizations

COMPETING INTERESTS

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

The author participated in the study design, coordination, and manuscript drafting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to extend my thank you very much to the Editor-In-Chief for his decision, two anonymous reviewers and the English proofreader diligently working on this manuscript.