Vocabulary learning strategies instruction: a case study of teachers’ practices and perceptions

- University of Social Sciences and Humanities, VNU-HCM

Abstract

Vocabulary Learning Strategies (VLS) are widely acknowledged to be effective in facilitating learners’ vocabulary acquisition and explicit instruction of VLS is required for learning to take place. Past studies indicated that Vietnamese EFL learners do employ various strategies to learn vocabulary, however, VLS instruction has not been as widely researched. Thus, a qualitative case study was employed with the aim of exploring the teachers’ practices and perceptions regarding VLS instruction. Four teachers were selected by maximal variation sampling. Twelve non-participant observations and four semi-structured interviews with four teachers were used to collect data. Findings revealed that the teachers had positive perceptions regarding VLS and VLS instruction. Furthermore, it was discovered that they had mixed opinions concerning the necessity of explicit instruction of VLS. Half of the teachers agreed that VLS instruction is necessary; however, they did not explicitly teach VLS. The other half argued against explicit instruction of VLS and merely employed VLS as a technique to explain the meaning of new words. This study thus concluded that there was a mismatch between the practices and perceptions of teachers, and from this, implications about the necessity of teaching VLS, vocabulary teaching practices, and teacher training were made.

INTRODUCTION

Background to the study

Vocabulary is considered “the heart of language comprehension and use” (Hunt & Beglar, 2005, p. 24)1, reflected in a famous remark by Wilkins (1972): “Without grammar, very little can be conveyed. Without vocabulary, nothing can be conveyed” (as cited in Schmitt, 2010, p. 3)2. Indeed, the importance of vocabulary has also been proven in various studies (Horwitz, 1988; Hunt & Beglar, 2005; Schmitt, 2010)3, 2, 1, leading to increasing interest in its learning, retention, and instruction.

Among these, vocabulary instruction has received special attention. Systematic vocabulary learning is beneficial for retaining and producing vocabulary (Min, 2013)4. Vocabulary can be learned implicitly or explicitly (Hunt & Beglar, 2005; Schmitt, 2000)1, 5, but explicit learning is considered more effective and leads to better retention and production (Hunt & Beglar, 2005; Nation, 2002; Schmitt, 2008)1, 6, 7. Consequently, explicit vocabulary learning and instruction are recommended in the vocabulary acquisition process.

Vocabulary learning can be assisted by Vocabulary Learning strategies (VLS), a sub-category of language learning strategies (Nation, 2013)8. Learners must know a wide range of strategies and choose appropriately (Nation, 2013)8 because their usability depends on multiple factors (Griffiths & Parr, 2001; Oxford, 1986)9, 10. Using VLS systematically and independently entails an awareness of the possible strategies through teachers’ instruction, which means VLS can be taught to learners (Griffiths & Parr, 2001; Le, 2018; Nation, 2013; Oxford, 1986; Singh, 2017)9, 10, 8, 11.

Despite their importance, VLS are largely under-researched in the Vietnamese EFL context. Local empirical studies established that Vietnamese EFL learners do employ strategies in their vocabulary learning (Do & Nguyen, 2014; Le, 2018; Nguyen, 2013; Nguyen, 2016)12, 13. However, in general, issues related to teachers, such as their strategy instruction, have not received as much attention (Griffiths, 2007; Nguyen, Le, & Ngo, 2021)14, 15. Strategy instruction helps students be aware of effective strategies and use them appropriately (Nguyen, Le, & Ngo, 2021)15, and teachers’ perceptions and practices are of utmost importance as they can potentially affect the effectiveness of the teaching and learning processes (Griffiths, 2007)14. Given this importance, there exists a need for more empirical studies on VLS from teachers’ perspectives.

Aims of the study

Considering the importance of teachers’ instruction on VLS and the gap in the literature, this case study, conducted at an English language center in Ho Chi Minh City, aims to investigate how they perceive and carry out VLS instruction in their teaching context. The findings can help provide some pedagogical implications which are potentially beneficial for the explicit VLS instruction at the research site.

To achieve those aims, the study attempts to answer the following questions:

-

How do teachers teach Vocabulary Learning strategies?

-

What are the teachers’ perceptions of Vocabulary Learning strategies instruction?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Aspects of vocabulary knowledge

It is assumed that knowing a word simply entails knowing its meaning, and to a certain extent, this is true (Henriksen, 1999; Schmitt, 2010)16, 2. Knowing a word, however, involves more than knowing its meaning (Nagy & Scott, 2000)17. Instead, vocabulary knowledge is conceptualized as consisting of multiple separate but interrelated aspects. Different frameworks of vocabulary knowledge have been proposed but perhaps the most comprehensive is that of Nation (2013)8, which proposed that at the most general level, knowing a word includes knowing its form, meaning, and use. Knowledge of form includes knowledge of both spoken and written forms of the word and knowledge of word parts. For meaning, the form-meaning connection is understandably the first component to master. Additionally, a knowledge of concepts and referents is also required. Finally, knowledge of vocabulary use entails knowledge of the word’s grammatical function, its collocations, and lastly, its constraints on use. This framework is further divided into receptive and productive mastery, and the end result is a list of 18 different aspects of word knowledge (Figure 1).

Aspects of vocabulary knowledge (Nation, 2013, p. 49)

Vocabulary Learning strategies (VLS)

Vocabulary Learning strategies (VLS) are part of language learning strategies, which are, in turn, part of more general learning strategies (Nation, 2013)8. Their exact definition remains a subject of debate but generally, VLS are the conscious behaviors, steps, or techniques employed by learners to enhance their vocabulary learning (O’Malley & Chamot, 1985; Oxford et al., 1989; Rigney, 1978)18, 19, 20. Oxford (1986)10 identified three main reasons why VLS are important for language learning. First, VLS are important because they are directly linked to learners’ performance. Successful learners often employ VLS more frequently and effectively compared to their less successful counterparts (Altmisdort, 2016; Simsek & Balaban, 2010)21, 22. Second, VLS help improve learners’ autonomy, enabling learners to take responsibility for their own learning, thus shifting the focus from the teachers to the learners (Oxford, 1986)10. Lastly, VLS are of great import because unlike other individual factors such as motivation, learning styles, attitude, or aptitude, learning strategies are teachable. Indeed, Mizumoto and Takeuchi (2009)23 found that explicit instruction of VLS resulted in an increase of strategy use among learners with low and moderate levels of VLS use.

Teachers’ perceptions and practices of VLS instruction

Importance of VLS instruction

Research on general learning strategies revealed that learners employed various learning strategies in different situations and the applicability of learning strategies is influenced by different factors (Oxford, 1986)10, which means a strategy may be useful in one context but not in another. Successful learners are aware of a wide range of strategies and use them appropriately to fulfill the learning tasks (Anderson, 2005)24. For this reason, guidance and instruction from teachers are necessary for learners to explore the possible strategies most beneficial to them (Ölmez, 2014)25. Anderson (2005)24 asserted that instruction primarily aims to “raise learners’ awareness of strategies and then allow each to select appropriate strategies to accomplish their learning goals” and the most effective strategy instruction is integrated into regular classroom instruction (p. 763). Learners need strategies to take full control of their vocabulary learning processes and accordingly, VLS instruction enables them to do this effectively and independently. Merely introducing the strategies to the learners, however, is not enough (Nation, 2013)8; instead, the instruction should be incorporated into vocabulary teaching with a specific amount of time. That being said, teachers receive little guidance on this aspect (Nation, 2013)8.

Webb and Nation (2017, in Webb, 2019)26 propose three principles for teaching VLS. First, teachers should raise students’ awareness of the benefits of VLS so that they are more likely to use those strategies frequently. Second, teachers need to train students to use VLS effectively rather than just introduce them to the students. Third, there should be a large amount of time spent on training and assessing the students’ ability to use VLS effectively. Teachers are responsible for providing instruction so that students can use VLS automatically in the vocabulary learning process and gain independence in their own learning (Ölmez, 2014)25. When selecting the VLS, teachers should take the learners and the learning context into consideration, including the learners’ proficiency level, their cooperation to learn, their motivation and purposes to learn the target language, and the nature of the target language (Schmitt, 2007)27.

Previous studies on teachers’ perceptions and practices of VLS instruction

One notable study exploring teachers’ perceptions of VLS is by Lai (2005)28. In this study, Lai (2005)28 examined Taiwanese EFL senior high school teachers’ awareness and beliefs of VLS and looked into the correlations between their beliefs and teaching practices. Findings from the study indicated that the teachers were aware of the various VLS but applied some inappropriately due to the lack of knowledge from relevant research. They also implemented more frequently the strategies they considered most useful. Nevertheless, there were some strategies considered useful but not introduced frequently in the classroom owing to contextual and learner factors.

In another study, Ölmez (2014)25 conducted a mixed-methods study to compare Turkish high school students’ and teachers’ perceptions of VLS and teachers’ practices of strategy instruction. It was revealed that the teachers attached great importance to the use of VLS for vocabulary development and the instruction of VLS for students’ independent learning and teachers’ self-development. Despite claiming to introduce various VLS to their students, the teachers encountered several obstacles such as class sizes, curriculum design, and time limitations. They also acknowledged that their instruction of VLS helped guide the students to discover the strategies that suit their interests and that the degree of students’ applications varied among students. Similar to Lai (2005)28, there was a positive correlation between the teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the strategies and their instructional practices. However, there was a mismatch between the teachers’ instruction of VLS and the students’ application.

Pookcharoen (2016)29 conducted a study with twenty-four university teachers to explore their beliefs about the usefulness of VLS and their instructional practice, using questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The results showed that there was a mismatch between the teachers’ beliefs and teaching practices, due to several factors including students’ English proficiency level and motivation, teachers’ vocabulary knowledge and instructional approaches, and time constraints, similar to those of Lai (2005)28.

Within Vietnamese contexts, Vu and Peters (2021)30 recognize that there have been few systematic investigations into the practices of vocabulary teaching and teachers generally do not train students to use VLS effectively. Nguyen, Le, and Ngo (2021)15 acknowledge scant attention to the area of strategy instruction but highlight the importance of teachers’ strategy instruction mentioned in the sections of pedagogical implications and suggestions in some studies. Some of those include raising students’ awareness of VLS and their usefulness (Duong, 2022; Phan et al., 2020)31, 32, allowing opportunities to practice and assess students’ use of strategies (Phan et al., 2020; Tran, 2020)32, 33, and motivating students to use VLS independently and autonomously outside the classroom (Duong, 2022; Tran, 2020; Phan et al., 2020; Vu & Peters, 2021)31, 32, 33, 30.

In summary, there have been a few studies conducted on the teachers’ perceptions and practices of VLS instruction. However, in the context of Vietnam, studies on VLS have mostly focused on students’ use of VLS and there has been very little research about teachers’ perceptions and practices of VLS instruction, although several implications related to teachers’ roles and strategy instruction have been put forward in the literature. Furthermore, as most of the existing studies collect self-reported data through questionnaires or interviews, there exists a need to carry out classroom observations in order to enhance the reliability and validity of the data. For those reasons, the current study is conducted using interviews and classroom observations to investigate teachers’ perceptions and practices of VLS instruction in the Vietnamese context.

METHODOLOGY

Research design

This study was conducted to seek an in-depth analysis of teachers’ perceptions and practices of teaching VLS; therefore, qualitative research was chosen. According to Creswell (2012)34, qualitative research allows researchers to explore a problem and develop a detailed understanding of a central phenomenon. Case study was adopted as the research design as it offers the opportunity to investigate a phenomenon within a real-world setting and can build a realistic picture of the issues under investigation (Bassey, 1999)35. Additionally, it is also appropriate as the small number of individuals involved will be easier to recruit and have permission to obtain information (Duff, 2011)36.

Participants

The study was conducted at a language center in Ho Chi Minh City. The students at this site are mainly at the age of 12 to 15 at pre-intermediate, intermediate and upper-intermediate level and the teachers can be responsible for teaching students at different levels. Four teachers were selected with purposeful sampling, specifically maximal variation sampling, to get multiple perspectives of individuals and have a diverse and thorough understanding of the perceptions and practices of teaching VLS in the classroom for students at different levels: pre-intermediate, intermediate, and upper-intermediate.

Research instruments

This study employed observations and semi-structured interviews. The alignment between the research questions and methods of data collection is presented in

Alignment between research questions and methods of data collection

|

Research questions |

Methods of data collection |

Data sources |

|---|---|---|

|

1. How do teachers teach vocabulary learning strategies to their students? |

Observations (12) |

The researcher |

|

Semi-structured interviews (4) |

The teachers | |

|

2. What are the teachers' perceptions of teaching vocabulary learning strategies? |

Semi-structured interviews (4) |

The teachers |

Classroom observation

The use of observation can provide more valid or authentic data (Cohen et al., 2018)37. Cohen et al. (2018)37 suggests that the researcher stays with the participants for a substantial period of time to address reactivity, the effects of changing behaviors of observees due to the researchers’ presence. Therefore, non-participant observations (see Appendix A for the guiding questions) were carried out in three weeks. The observation sheets were completed during the observations to minimize the problem of selective memory.

Semi-structured interviews

Besides observations, interviews were considered a powerful tool to collect qualitative data, explore issues in depth and understand why people hold the ideas for what they do (Cohen et al., 2018)37. Hence, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews, where the questions are open-ended with prompts and probes (Cohen et al., 2018)37. There were three questions in the interview to explore their perceptions about VLS instruction and some prompts and probes for participants to elaborate on their answers (Appendix B).

Data collection and analysis procedure

Data collection procedure

First, classroom observations were conducted by one of the researchers to explore what and how VLS were instructed in the classroom. He observed one specific class of each teacher three times. Consequently, twelve observation fieldnotes were collected after three weeks. Afterwards, the teachers were individually invited to attend online interviews on Zoom platform. All interview sessions were recorded to assist the subsequent data analysis.

Data analysis procedure

Firstly, all interview recordings were transcribed using Cockatoo. To make it easier to keep track of the documents, the interview transcripts and observation fieldnotes of each participant were given a code, presented in

Codes of data

|

Participants |

Codes | |

|---|---|---|

|

Observation fieldnotes |

Interview transcripts | |

|

Teacher 1 (T1) |

O1.1 |

I1 |

|

Teacher 2 (T2) |

O2.1 |

I2 |

|

Teacher 3 (T3) |

O3.1 |

I3 |

|

Teacher 4 (T4) |

O4.1 |

I4 |

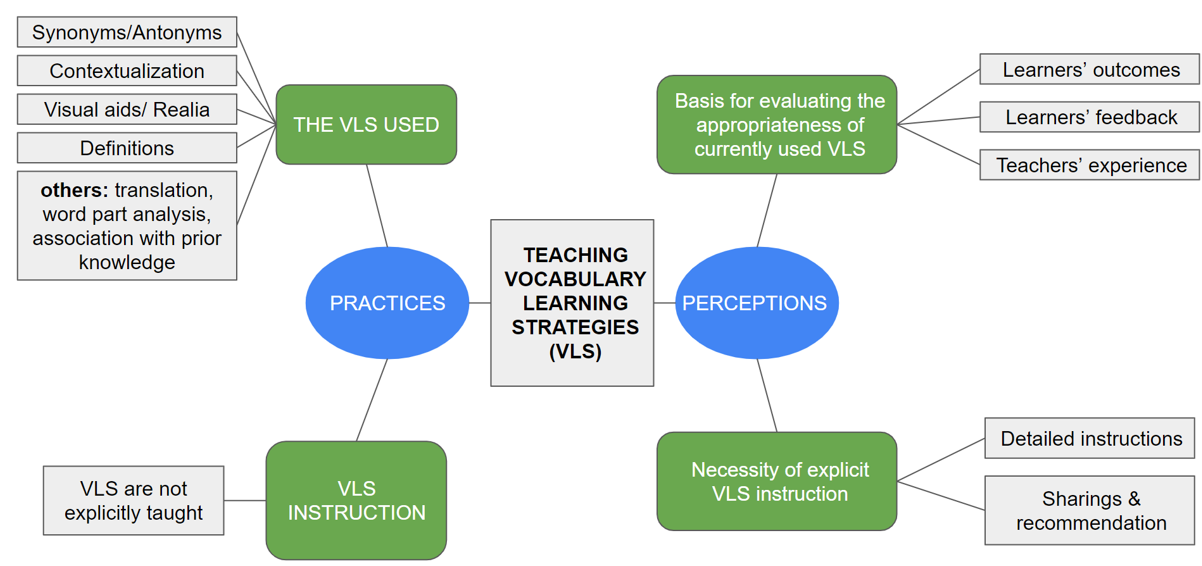

Thematic analysis was employed to analyze and create themes from the observation fieldnotes and interview transcripts. The study identified two main themes with some supporting themes and subthemes, all of which are presented in the following thematic network (Figure 2).

Thematic network of the study

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Findings

Teachers’ practices of VLS instruction

The data from the observation sessions revealed that the teachers did not explicitly instruct VLS, but rather used them to teach vocabulary.

The frequency of each VLS employed by the four teachers

|

Vocabulary learning strategies |

Teacher 1 |

Teacher 2 |

Teacher 3 |

Teacher 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Synonyms/antonyms |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

|

Contextualization |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

|

Realia |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

|

Definition |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

frequently |

|

Translation |

frequently |

rarely |

rarely |

frequently |

|

Word part analysis |

frequently |

rarely |

sometimes |

sometimes |

|

Association with prior knowledge |

never |

never |

rarely |

never |

As clearly shown in

The next strategies were using realia and definition. All of the teachers tended to use visual aids, specifically pictures, to convey the meaning of new words. For instance, to explain the noun “countdown”, T1 simply showed the students a photo of a New Year’s Eve party and elicited responses from the students (O1.1). Additionally, albeit not as frequently as the other strategies, definitions were used to teach complex words or phrasal verbs. For instance, T1 provided the definitions of words and phrases such as “punctual” and “cut down on” (O1.1; O1.2). Other teachers, like T2, explained the phrase “go on an expedition” by giving the students the meaning of the noun “expedition”.

Finally, there were other strategies that were employed by certain teachers including translation, word part analysis, and association with prior knowledge. T3, for example, translated the word “optimistic” into Vietnamese (O3.1). Regarding word part analysis, T2 would explain the word “unfriendly” by analyzing the prefix “un-”, meaning “not” or “against” (O3.1). For associating with prior knowledge, only T4 was reported to employ this strategy during one session (O4.1).

Teachers’ perceptions of VLS instruction

The study discovered two thoughts on the need to explicitly teach VLS. On the one hand, T1 and T4 highlighted the importance of VLS for lifelong learning since they empower students to learn outside of the classroom without the teachers’ assistance. Hence, VLS instruction cannot be ignored in an English class.

(I4).

On the other hand, T2 and T3 assumed that VLS should be briefly introduced as a strategy to broaden vocabulary size, but not as a compulsory part of teaching in class. It is argued that VLS catered to certain learning styles and priorities (T2), so it was better for students to explore VLS by themselves (T2, T3). Hence, it can be concluded that the teachers showed less consensus on the need for VLS instruction.

Students’ language abilities and cognitive levels were reported to be the most popular criteria used by the teachers when evaluating the suitability of their currently used VLS. Also, the study obtained other useful techniques from T1 and T2. T1 tended to check the appropriateness of VLS through He would also gather feedback from his students through informal and formal assessments, observations and even in open communication. T2 suggested relying on the teacher’s experience and the students’ performances.

In a nutshell, the necessity of explicit instruction on VLS is acknowledged with a slight discrepancy among the teachers in the extent to which VLS should be instructed in class. They also mentioned some ways to evaluate the appropriateness of the VLS they are currently using for their classes.

Discussion

Teachers’ practices of VLS instruction

The teachers were found to use a wide range of VLS with diverse combinations in their vocabulary teaching practice, like those in Ölmez (2014)25. Such integrations can be explained by several factors pointed out in previous studies (Lai, 2005; Pookcharoen, 2016; Schmitt, 2007)28, 29, 27 such as time constraints, targeted vocabulary, lesson objectives, learners’ proficiency, and teachers’ instructional approaches. Also, the use of various VLS is believed to raise the learners’ awareness of the available VLS so that they can choose which VLS fit them the best (Anderson, 2005; Nation, 2013; Ölmez, 2014)25. It could be inferred that the majority of those strategies were employed by the teachers to illustrate the forms and meanings of vocabulary like its word parts, referents, and associations, the receptive aspect of vocabulary knowledge as in Nation’s (2013) framework. There was an absence of focus on deeper levels such as collocations and registers. Even contextualization was utilized to elicit the meaning of new words, not to help the students understand the use of those words in that particular context. As a consequence, despite the variety of strategies used, the students may understand the meaning but lack the productive knowledge of vocabulary as they do not know how to use it.

Also notable is a mismatch between how the teachers perceived the importance of VLS instruction and what they really did in class. The teachers were found not to provide explicit instruction about VLS, instead, they made use of the strategies as a means to teach new vocabulary, or offered a quick introduction to the students, which seems to have no impact on the learners’ autonomous use of VLS in their self-study (Nation, 2013; Webb, 2019). It could be explained by the fact that the teachers may not be fully aware of how to teach VLS effectively, as Nation (2013) acknowledges that there is little research providing guidance for teachers.

Teachers’ perceptions of VLS instruction

While all of the teachers appreciate the benefits of VLS, they held different thoughts on the necessity of VLS instruction. One group highlighted that it was vital to provide students with clear guidance on VLS. However, the others advocated a quick introduction to VLS, arguing that students should be allowed to decide on suitable VLS by themselves instead of involving in a detailed instruction of all strategies. This could be explained that there exist several factors that can hinder the explicit teaching of VLS, such as students’ learning styles, motivation, objectives, and learning contexts outside the classroom, as suggested by Schmitt (2007)27. Nonetheless, Nation (2013)8, Anderson (2005)24, and Ölmez (2014)25 do not support such a claim. They emphasize that learners need comprehensive training from teachers to be clearly aware of the available learning strategies to ensure the effective use of VLS. T1, considered to be the most knowledgeable and experienced one, also agreed that VLS should be systematically taught to students and the effectiveness of VLS instruction must be assessed by certain techniques.

Besides concerning the alignment between the used VLS and students’ proficiency level, the teachers are recommended to use different techniques to thoroughly evaluate the appropriateness of VLS instruction. Some techniques that were advised in the study include the use of formal and informal assessments to test students' use of VLS, students’ oral or written feedback, and classroom observations. However, among the four teachers, only T1 attempted to use those techniques in his class. Thus, it can be inferred that the teachers have not given enough consideration to the assessment of students’ capacity to use VLS, which is deemed highly important in VLS instruction (Nation, 2013; Webb, 2019)8, 26.

CONCLUSION

The findings have provided insight into teachers’ practices and perceptions of VLS instruction. Some VLS were employed by the participants when teaching vocabulary but were not explicitly taught to the students. Regarding perceptions, not all of the participants thought VLS should be taught explicitly but should only be recommended to their learners. Overall, there is a discrepancy, to a certain extent, between their perceptions and practices regarding VLS instruction.

There are some implications for teachers and teacher trainers. Considering the acknowledged benefits of VLS, teachers should emphasize the necessity of using VLS and instruct students to effectively employ certain strategies appropriate for their level and learning styles. There should be demonstration, practice, and evaluation of strategy use in VLS instruction. Teachers can combine different VLS to maximize their effect and experiment with certain VLS to evaluate their suitability. The findings also illustrate that teachers often focus on enhancing students’ receptive vocabulary knowledge rather than their ability to produce vocabulary. This highlights the need for more training on vocabulary production and use, such as teaching collocations, registers, and word usage. In other words, once students have mastered the form and meaning of words, teachers should focus on expanding their vocabulary knowledge in usage for productive skills. It is also essential that VLS instruction be introduced to teachers in regular workshops and training sessions. Moreover, teachers and teacher trainers should discuss how to incorporate VLS instruction into their daily lessons with the use of games and activities for students’ independent learning.

Regarding the limitations, this case study involved a small number of participants due to their availability and time constraints. It is recommended that a larger sample be obtained in various teaching contexts to provide a richer description of teachers' perceptions and practices of teaching VLS. Further studies might also include students’ perceptions of teachers’ VLS to investigate the usefulness of these strategies and their difficulties when using VLS.

APPENDIX A: Guiding questions for observation

1. How were new vocabulary taught?

-

The steps to teach/ introduce new vocabulary and duration of each step -

Use of materials, teaching aids, tools, or realia (if any) -

Language of instruction: L1, L2, or both? -

Use of concept-checking questions (to check students’ understanding of the concept) and instruction-checking questions (to check students’ understanding of the instruction provided)

2. How were VLS taught?

3. Are there any unexpected incidents/ occurrences during the lesson?

APPENDIX B: Interview questions

-

What are the levels of the students that you are currently teaching?

-

Do you think the vocabulary learning strategies you are currently using are appropriate for the level of the students in your class?

-

In your opinion, should teachers explicitly teach vocabulary learning strategies to their students? Why (not)?

Biodata

All of the four authors are studying the Master’s program in TESOL at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities. They all share the same interest in the studies of English linguistics and language learning strategies.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.